The Museum of Modern Art’s Miraculous New Online Archive

Every exhibit since 1929 can now be seen for free—and the effect is unsettling.

Look at the picture above, and find the plant.

It is a dentist’s waiting room plant, too droopy even for an aunt’s windowsill, but there it is, keeping watch over Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. The plant isn’t art. It’s not on the curator’s checklist for the exhibition. (I checked.) I don’t know why it’s there. But in the Museum of Modern Art’s straightforwardly named 1947 show, “Large-Scale Modern Paintings,” the plant got a front row seat.

It’s one of the many mysterious specifics revealed in a huge, new archive of curatorial photographs and documents that the museum made available Monday. This archive, available for free on the Museum of Modern Art’s website, now documents every show that it has exhibited, going back to its very first in 1929.

For art-history fans and scholars, this archive uncovers the lineage of an organization that has “defined Modernism more powerfully than perhaps any other institution,” as the Times puts it. And, surely, graduate students will consult its pages for years to come. But this is a remarkable project, and browsing through it will reward many more people than just scholars. These are stunning, discomfiting photographs, and they seem both recent and ancient at once.

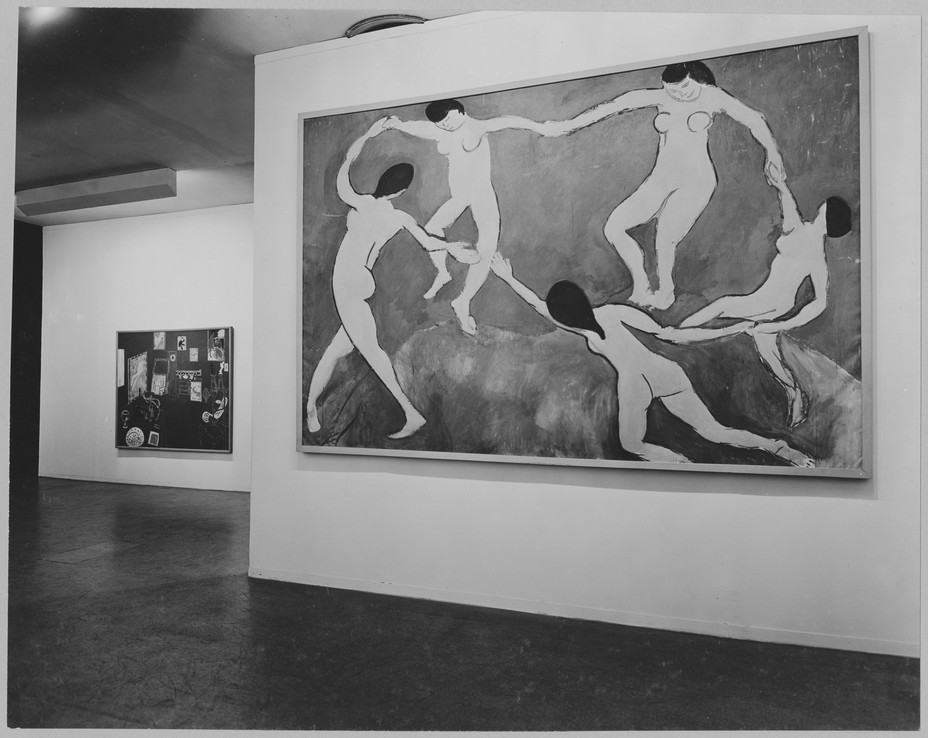

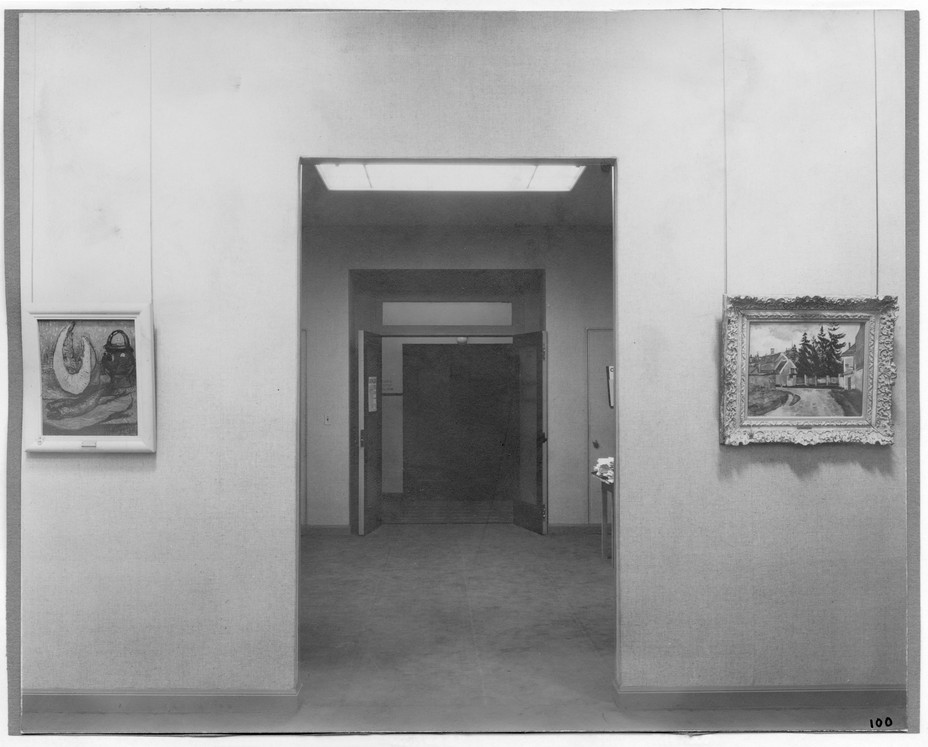

The photos are almost all spare and without people. They seem to have been captured for documentary purposes, not expressive ones. Professionals took them to remember whom they hung across the room from whom, a kind of visual note-taking that any contemporary smartphone user will recognize.

The sum effect is disarming. Van Gogh’s painting of his bedroom in the photograph below, for instance—an image of the museum’s first major exhibit, in 1929—is one of the three famous paintings of his bedroom that exist. You have probably seen this one in textbooks and on television. But here, crowded against one wall in a dusty room, and without any people gathered around it, it loses its familiarity. It is like seeing a photo of a friend from before you met them.

The Times describes MoMA’s 87-year history as “a procession of solemn white-box galleries.” But these photos gently push at the idea that the art museum’s white boxes are immutable or immune to fashion. In 1929, paintings hang from the ceiling, and the floors are hardwood. Thirty years later, paintings seem to hover against the wall, and ambient lighting fills the room and reflects off marble floors. The museum quietly gets wealthier, and its subject more institutionalized.

The professionals who directed the museum are largely unseen in the gallery photos, but they are hiding in the archive’s PDFs and curatorial additions. Anyone with a web connection, for instance, can now examine, room by room, the 19 exhibits that the poet Frank O’Hara curated for his day job. Without looking very hard, I was able to find his introduction to the 1960 exhibit he directed, “New Spanish Painting and Sculpture.”

“If the motto of American art in recent years can be said to be ‘Make it new,’ for the Spanish it is ‘Make it over,” he wrote. “For the authentic heir of a great past the problem is what to do with it, whereas the authentic artist’s problem in America is that of bare creation with whatever help from other traditions he can avail himself of.” He published Lunch Poems four years later.

It is the 1929 show, an exhibition of Cézanne, Gauguin, Seurat, and van Gogh, that really grabs me. So many works now-iconic works, works that have acquired an easy visual currency, are here just hanging from the wall.

Of course, all iconic paintings are just hanging from the wall. But that’s part of the power, too. There are untrammeled rooms like this today, in the bowels of every academic art museum or archive in the country. The fact that the room is empty makes it all the easier to imagine yourself in the small gallery, and the density of famous images makes the scene poignant.The urbane and unfazed curators who set up this show seem not so far from people you still might find in an art museum. Their unexplained choices, their unseen temperament, feel, well, modern. I can imagine them standing shoulder-to-shoulder with a visitor, inspecting a brush stroke, saying something funny and cruel about the artist’s love life.

Yet in between these people and ourselves looms the rise of fascism, the slaughter of 60 million, the invention of nuclear weapons, the electric typewriter, the color television, the microchip, the network, the cellphone. These photos were taken by people like us, but they are separated from us by an unfathomable distance. This new archive of MoMA’s is an exhibition of ghosts, created by ghosts.